History

Mousehole History

Mousehole (pronounced Mowzel), sits on the Western shore of Mount’s Bay, cradled in the mouth of a steep south-facing valley.

Looking east, to what were known as the ‘eastern lands’, the village sits on either side of a small stream, which flows down hill from the village of Paul cutting a valley between two varieties of rock: granite on the western side and greenstone (known locally as blue elvan) on the other. A combination of scale and setting makes it one of the loveliest harbours in Cornwall, with spectacular views across Mount’s Bay, which is still dominated by St Michael’s Mount. To wander around this typical fishing village on a warm summer’s day is to take a step back in time, but this air of casual ease is deceptive, for Mousehole was not always a sleepy village.

There is no evidence of a permanent settlement in Mousehole before about 1200 but the village has probably been part of the parish of Paul since Anglo-Saxon times.

In October 1242, when Richard, earl of Cornwall, was on his way home from Bordeaux in France, his ship nearly foundered in a storm off the coast of Cornwall and he feared for his life. In the event, his ship reached safe harbour, but Richard did not forget his narrow escape and it was to have important repercussions for the place where he landed. That place, a natural inlet in the steep cliffs of far-west Cornwall, was ‘the hole of the mouse’ (in Latin used by the chronicler of the event, pertusum muris) which today we call Mousehole.

The earl was an important man. The younger brother King Henry III of England, he went on to marry Sanchia of Provence, sister of Henry’s queen, the year after the storm. King Henry III gave his brother Cornwall as a birthday present, making him the High Sheriff. His safe landing mattered in the history of Mousehole as it ensured that its name, unusual in west Cornwall because it derives from English, was first mentioned in written resources.

In 1556 (300 years after earl Richard’s safe landing). Mushol (Mousehole) was still the first port in the English Channel. By the Middle Ages Mousehole was known as Musehole showing that it contains Middle English mus ‘mouse’. Two parts of Mousehole had the Cornish names of Porthenys and Porthengrouse, ‘island harbour’ and ‘the cross harbour’.

Spanish Invasion - The Mousehole Raid

In the late 16th century there was little pretence of friendly relations with Spain, and in 1584 the 20 year war began. Fears of an invasion grew and Cornwall, the nearest point to Spain, became the country’s most vulnerable outpost.

In July 1595 a squadron of four Spanish galleys set sail from Brittany with orders to prepare a feasibility study for a large scale attack on the English coast. Under the command of Captain Carlos de Amezola, Richard Burley, a catholic defector familiar with Cornwall, guided the mission. Two prisoners, Barnaby Loe and Robert Kettle, were coerced to act as pilots.

As dawn broke on 23 July the rising sun revealed a calm emerald bay backed by dark moorland hills. Richard Burley recognised Mount’s Bay and the cluster of cottages under the western cliffs as Mousehole. Captain de Amezola decided to raid the town. Surprise was complete. There was no signal beacons and no warning guns on St Michael’s Mount; only the splashing and the clink of armour and weapons broke the stillness. Accounts of attacking force’s vary, but there were at least 400 pikemen and harquebusiers (The first cavalrymen to be armed with firearms were known as harquebusiers. The name derived from the word ‘harquebus’, which was their main weapon.) The unarmed local population fled in panic towards Paul & Newlyn. Squire Jenken Keigwin, who had built a fine granite house in the village in the mid 1500’s, was killed, reputedly making a stand to protect his home. Keigwin Manor still survives today. The village was sacked and set alight by firing parties which then, unopposed, marched up to Paul where they burned the houses and the church.

On the third day the Spanish, fearful of Drake’s fleet, took advantage of favourable wind and made off to Brittany… never to return.

Markets & Fairs

A charter for a market to be held on Tuesday’s was granted in 1292, and another charter was granted for a three day fair to celebrate the feast of St Bartholomew in 1313.

Mousehole Quays

Before the late 14th century the ports of Mount’s Bay relied entirely upon natural harbours and anchorages. Mousehole was very exposed and in the 1390’s the villagers asserted that there had been ‘no port for ships to rest securely in, whereby many have been wrecked’. In consequence, it was the first port to construct a protective pier or quay.

The first pier at Mousehole was built in 1387-93 as ‘a defence against the sea’. Large beach boulders were used and still survive in the middle section of the inside face of the South Pier – major repairs were done to this pier in 1435 & 1555.

The original quay, readily distinguished by the massive stones, ended at the part once known as “the old stairs.”

In 1837, the harbour was found to be too small for the number of boats, and a first attempt was made to create a more enclosed harbour. It was decided that the old “or inside” little quay that carried out from the Ship Inn adjoining Uncle Billy Burdo’s cellar should be removed.

The granite stones from this pier were recycled in 1868 to 1871 and used to build the new northern pier – the present harbour as we know it was designed by Sir James Douglass, the great lighthouse engineer (Eddystone Tower, Wolf Rock). The granite quays were the work of Freeman and Sons, a Penryn-based firm, at one time the biggest granite working and exporting business in Britain.

A slipway of Sheffield or Lamorna granite opposite the harbour office and town clock was created in c.1855 at the expense of John Garrett, vicar of Paul.

Mousehole quay was then copied by other Mount’s Bay ports, including Penzance, St Michael’s Mount and Newlyn.

Mousehole Harbour is not naturally sandy, so every spring, sand is imported to provide a clean and safe beach environment. In the not to distant past, when streams, culverts, drains and sewage discharged directly into it, the harbour floor was mud and shingle.

Mousehole Fishing

Fishing and pilchard processing was the villages main occupation for centuries.

The four month pilchard season started in July and every available person was needed to get the fish landed and into the cellars. There the pilchards would be ‘bulked’ – layered up with salt on the cobbled floor and left for four or five weeks. Fish oil, blood and brine were drained along channels into ‘train pits’ lined with a cask. The ‘train oil’ skimmed from the top was sold for lighting and manufacturing use.

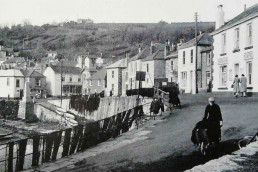

At the height of Mousehole’s prosperity, drift nets hung to dry all along the harbour. Old men & fisherman gathered in groups to yarn and pass the time of day on The Cliff, walking back and fore, the length of a boats deck. This practise was referred to as being on the ‘gow’ – Cornish for gossip/lies.

Drift nets needed constant attention and maintenance and fishermen spent a lot of their time barking, drying and preserving their nets until the introduction of synthetic fibre nets in the 1950’s.

Until the middle of the 19th century the barking of nets was done by immersion in a hot preservative substance made principally from the bark of the native oak and birch trees. After that cutch from the east such as India and Borneo was used.

In India ‘cutch’ was made from the bark of Acacia trees by stripping the bark and boiling it in water and the thickened extract was decanted into iron pots and boiled again until it attained a syrupy consistency. Then it was poured into moulds and exposed to the sun and air until it hardened into a dark brown substance.

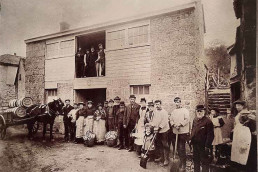

The old Barkhouse in Mousehole is situated just off North Cliff up a small side lane ~ it would have been a hive of industry during the early 19th century.

In early October 1866 immense catches of Pilchards were reported in Mousehole & Mount’s Bay. A careful calculation of the catches gave the supply at 7,000 hogshead.

A hogshead of pilchards contains from 2,500 to 3,000 fish, and these, when fresh, weigh about 6.5 cwt. Taking the number at 2,500, the result of the week’s fishing was about 17.5 million pilchards, weighing upwards of 2,200 tons. If all were disposed from the boat’s side at 30 shillings per hogshead, their monetary value would be £10,501.00!

But there was no demand at home for such a large quantity of pilchards so they were bulked (salted) for exportation. The quantity of salt required for the cure of this large catch was nearly 1,000 tons. Bulking was mostly performed by the women, wives and relations of the fishermen.

The process of bulking begins with placing a layer of salt on the floor of the cellar, upon this a layer of fish is carefully placed, more salt, and then another layer of the fish, until a compact mass is built nearly breast high. The work proceeds with great rapidity, but every fish is individually dealt with, and any damaged are rejected. There they remained for about six weeks, when they were taken from the bulk, the salt washed off, and, once cleaned, they were placed in hogsheads for exportation.

14 shiploads departed Mousehole within a week – the pilchards were sent to the ports of Genoa, Leghorn, Civitavecchia (for Borne), Naples, Venice, Ancona, and Trieste, then distributed throughout the whole of Italy.

And in the words of the Mousehole people of that time… ’Long may the Italians continue to esteem these delicacies and may we ourselves never lack a “star-gazing pie’ in the fall of the year, and well stored bussas (large salting pots) in the winter’.

The fishing industry 1875 to 1925 was a well established way of life. Nearly every family in the town was involved with it in one way or another. The percentage of the population actively employed in fishing was greater in Mousehole than any of its neighbours at Newlyn or St Ives, where larger fleets existed.

Life was hard, particularly so for the wives who not only ruled their invariably large Victorian families, but also assisted with the mending of fishing gear and processing Pilchards, the result of the men’s labour. The men spent much of their time away from the family, either on longer fishing trips or at foreign fisheries.

Mousehole Regatta & Harbour Sports

Mousehole Regatta & Harbour Sports was founded in 1889 by Richard Treeve Harvey & Bruce Wright who were both Harbour Commisioners. It was a very important date in the towns calendar.

On Saturday 27th July, 1889 the town of Port-Enys (now commonly known as Mousehole) presented a gay appearance. There was a full display of bunting on the pier and at Lynwood, in honour of the first regatta for this Portus Insulae (Harbour/Port of the Island).

The 1890 Regatta & Harbour Sports records that running races for boys and girls on the northern pier took place with difficulties: the large crowd of fathers, mothers, brothers, and sisters yielding (to say nothing of uncles and aunts) but a narrow lane for the race-course, making the task of one competitor passing the other extremely difficult. However all passed off with good temper and a capital afternoon’s amusement was closed at eventide with a huge bonfire on the island and select music by the band.

In 1945 the highlight of the afternoon’s events was the greasy pole (seen in the 1949 photo extending from PZ 107 Renovelle) No one succeeded in walking it, although several got across one way straddling the pole and heaving themselves along, thereby plastering their legs and swimming trunks with grease. The winner was Jack Beare, who made a dash for it and ran half-way across before falling into the water.

St Clement’s Island

A chapel dedicated to St Clement, patron saint of mariners and sailors, once stood on the island just outside the harbour – hence the name St Clement’s Island. It is clearly shown on a map from 1515 and may have served as a lighthouse in c.1538.

‘Carn Lodgia’ stands on the highest point of the island, a monument known locally as the ‘Pepperpot’. It has been in position since 1869 and bears the initials of T.B.B and dates back to the time when Thomas Bedford Bolitho became Lord of the Manor, claiming with it the Island’s title. He desired to have his stone placed on top of the former claimants stone, Mr Halse. The island is still owned by the Bolitho family.

The granite stone, which weighed about 5cwt, was carried on board a punt by hand-barrow, and rested on the thwarts – it was then rowed to the island by four good Mousehole oarsmen and after some pulling and shoving was placed in position!

In 1990, 121 years after it had been installed, the stone monument on Carn Lodgia was toppled from its lofty perch during the winter’s violent storms.

May Bank Holiday Monday 1991 saw the Bolitho stone returned to its original position on top of the Halse stone. The pepperpot was replaced by local boys Stephen Payne, Paul Dodd and Andrew Wheeler. They had borrowed scaffolding from stone masons, Alan and Duncan Johns, and endless chain tackle from Bob Carswell – the equipment was taken to the island by boat and with much effort the stone was placed and lined up in its old position on a bed of cement… it has remained there ever since!

Boat Building In Mousehole c1890

The Wharf area is one of the oldest surviving parts of the village. All of the waterfront buildings were originally commercial, most having fish cellars, or workshops, at ground floor level. Boat building and repair was the order of the day, with large, seagoing ships moored to the blocks of granite dotted along the seaward side of the path. Several boats were built on the Wharf at Mousehole.

When a boat was launched from the builders yard a man was engaged for a shilling to supervise and ‘holla’ the rhythm for the other men to haul the boat to the water. The chant was, ‘Alaw – boat haul, Alaw – boat haul, Haul…Haul’. This would get the boat moving and as soon as some momentum had been achieved ‘Stamp and go… Stamp and go’. William Williams, father and son, were the builders – William senior built by rule of thumb, set up three frames, midship, bow and quarter, put up his ribands and moulded the other frames by the ribands.

His son, who built the Cornish Lugger PZ 156 Ganges for William Pezzack and N.G.R. Laity, had it laid out on a moulding floor. She was launched in Mousehole in 1873 and fished Cornish waters for 13 years.These luggers were extremely fast and seaworthy and could sail 45° into the wind. One, the ‘Mystery’ sailed from Newlyn, Cornwall via the Cape to Australia in 63 days when big schooners were taking 100 days.

William Pezzack remembers the launch day in Mousehole ‘It was a great time for all the village. There was tea for the crew and builders with a Launching Cake. In drinking days, before Teetotalism arrived in the village, there was a jar of beer alongside’.

Goods of every shape size and description were unloaded on the Wharf. Merchants and agents of various nationalities were engaged in the cosmopolitan trade. In common with the Old Quay in Newlyn, this served as an embarkation point for pilgrims to Santiago de Compostella in northern Spain.

Protecting Mousehole Harbour

During the winter months Mousehole Harbour closes to all vessels. From October / November until early April large individually numbered wooden baulks are placed in the gaps to protect Mousehole Harbour and the village from storm surges.

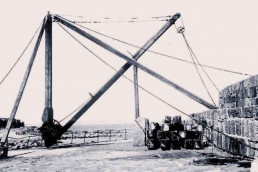

Prior to 1974 Mousehole had its own wooden crane, positioned on the end of the South Quay. On the night of 1st November 1907, the crane was used to hoist the Lady White over the baulks when the Thames barge ‘Baltic’ ran aground on St Clement’s Island.

The old crane was installed in 1873/74 and was regularly used up until 1974 when health and safety laws deemed it no longer a viable insurance risk. Ironically, the replacement metal crane collapsed during its first use and was removed permanently.

Wrecks, Lifeboats & Lifesaving

Baltic Rescue, St Clement’s Island, 1907

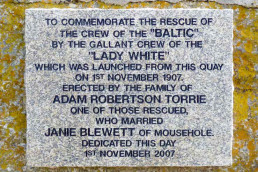

On the 1st November, 1907 – in darkness and very poor weather – the Thames sailing barge ‘Baltic’ went aground on St. Clement’s Island just off Mousehole Harbour… above the wind & waves the cries of the Baltic’s crew could be heard from the village.

Adam Robertson Torrie, from the Scottish Borders, founded another lifeboat dynasty and branch of the Blewett family as a result of this wreck – he was a mate on the Baltic.

The lifeboat was summoned but it did not arrive. Six village men Stanley Drew, Dick Thomas, Luther Harvey, Harry Harvey, Richard Harry and Charles Harry, a very brave & resourceful bunch, decided to organise their own rescue – they piled into the crabber Lady White to go to the rescue. But before they could row out of the harbour, the crabber had to be hauled over the baulks that had been lowered across the entrance because of bad weather, and then hoisted by crane to the other side.

They eventually found the survivors, including the captains wife and daughter, huddled and shivering in the shelter of the rocks. The Cornishman reported that: ‘One by one they were landed amidst rounds of cheers and taken to various homes by Mousehole folk who are ever willing to give food and lodging to those in trouble’.

Adam Torrie stayed at the home of Mousehole Harbour Master Francis ‘Frank’ Blewett, where he fell in love with and later married Janie, Frank’s sister. Barry Robertson Torrie who lost his life on the Penlee Lifeboat Solomon Browne on 19 December 1981 was their grandson.

The Penzance lifeboat Elizabeth & Blanche (II) had not been able to go to the aid of the stranded vessel. She became stuck on her carriage in the mud at low tide in Penzance Harbour. Despite having 10 horses, and countless helpers, the carriage remained stuck in the mud for an hour until the tide came in.

The six Mousehole fishermen, who gallantly rescued five persons from the wrecked barge Baltic were awarded £2 each by the local branch of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution. The men also received handsome silver medals, given by Mr. WJ Renfree Pellow, of Birmingham. These bore representations of a pair of oars and a lifebuoy, and on the back were the names of the wrecked boat and the place where the wreck occurred, while in the gold centre on the face of the medals were the names of the recipients, and the words “FOR BRAVERY”

Warspite Rescue, Prussia Cove, 1947

On the 23rd April 1947, crowds of people on the sunlit cliffs of Prussia Cove, in Mount’s Bay, saw eight men jump for their lives when the 31,000-ton former battleship, HMS Warspite, crashed against the rugged Cornish cliffs.

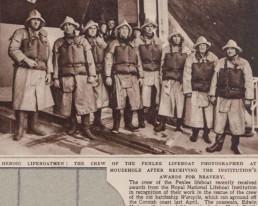

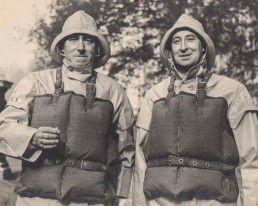

At the helm of the Penlee Lifeboat ‘W and S’ for the first time, was Mousehole man Coxswain Edwin (Eddie) Madron, who handled his craft with such skill that all were able to make the dangerous leap without injury.

The Grand Old Lady was on tow to Glasgow when the storm that scuppered her blew up off Cornwall.

“She was on a dead lee shore,” Mechanic Johnny Drew said. “The weather was very bad with a heavy sea running and the weather forecast was still bad. The wind veered southwest during the night and increased to force 10. When daylight arrived on April 23, Mount’s Bay was just one mass of white foam, nothing but heavy breakers”.

Coxswain Madron was awarded the silver medal of the RNLI and mechanic Johnny Drew received the bronze medal. The remaining crew of Mousehole men, Abraham Madron, Joe Madron, Ben Jeffery, Clarry Williams, Jack Worth, Luther Oliver, Jack Wallis, and Charlie Edmonds all received the thanks of the RNLI on vellum.

Edwin Madron, Coxswain Madron’s grandson, later became the Mousehole harbour master. He also gave 33 years service to RNLI Penlee, serving as crew on the Solomon Browne lifeboat, and as mechanic and second coxswain on the Mabel Alice. His brother Stephen Madron also became a lifeboat mechanic, losing his life on the Solomon Browne on the 19th December 1981. Stephen also served as deputy harbour master.

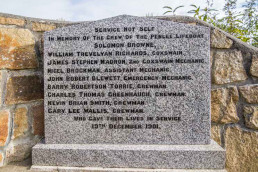

The Tragic Loss Of The Solomon Browne

On 17th September 1960 – a cold and blustery day – several hundred people crowded on to the Old Quay in Mousehole to watch Lady Tedder officially name the Solomon Browne lifeboat.

During the ceremony there was a sharp intake of breath when the champagne bottle hurled against the lifeboat did not break first time. Coxswain Jack Worth quickly stepped in to smash it with a hammer!

During her service the Solomon Browne lifeboat launched 238 times and saved 96 lives. Penlee lifeboat station was named after Penlee Point, a rocky tip to the south of Penzance, Cornwall, between the port of Newlyn and the village of Mousehole.The area has a strong lifesaving tradition stretching back more than 200 years: Penzance lifeboat station operated between 1803 and 1917, while Penlee has been open since 1913. Both are gilded with RNLI awards in recognition of outstanding rescues, not least an amazing 40 Medals for Gallantry.

It was at Penlee Point that the crew of the Watson class lifeboat Solomon Browne launched down the slipway for the last time on the evening of 19 December 1981.

At 8pm that night the Watson class lifeboat Solomon Browne ON954 met 15-metre waves and hurricane-force winds as she battled towards the Union Star coaster. The vessel had suffered power failure and was drifting towards the rocky Cornish shore. By now neither the Navy helicopter nor the tug that had also come to her aid was able to get close enough in such conditions. Reaching the scene at around 8.45pm, Coxswain Trevelyan Richards made repeated attempts to get alongside and take people off the Union Star. Once, the lifeboat was thrown on top of the coaster only to slide off into the next towering wave. Success came after 35 minutes with the transfer of four people.

The night was to end in tragedy…the helicopter crew could see that the lifeboat crew had some survivors aboard but that there were two people still on the coaster and one, if not two, in the water. Then, moments later, at 9.21pm, they heard over the radio:

‘Falmouth Coastguard, this is Penlee lifeboat, Penlee lifeboat calling Falmouth Coastguard’.

‘Falmouth Coastguard, Penlee lifeboat, go’.

‘We got four men off… look, er hang on… we got four off at the moment, er… male and female. There’s two left onboard…’

The message ended abruptly, but Lt Cdr Russell Smith, at the controls of the helicopter, could see the lifeboat, still apparently under control and heading out to sea. He took this as his cue finally to lift his aircraft out of the dangerous area where she had been hovering for so long and head back to Culdrose. He had assumed the lifeboat had made the same decision to turn for home.

At this point, there was only one other witness left: the tug Noord Holland, standing off, about a mile out to sea. Her skipper, Guy Buurman, listening to the vain attempts by the Coastguard to regain radio contact with the lifeboat, could see Union Star, the casualty vessel, right up close to the cliff and, intermittently, the lights of the lifeboat. His last view of the lifeboat was when she appeared high on the crest of a wave, silhouetted against the coaster’s lights.

Minutes later, the ship suddenly went dark: possibly the moment she was at last tumbled over at the foot of the cliffs. By the time cliff rescue teams arrived at the scene, the Union Star was already wrecked at the foot of the cliffs and there was no sign of the lifeboat. When she was eventually found, the wreckage gave no real clues as to what happened other than that she was ultimately subjected to the most shattering and violent force imaginable. The largest portion of the lifeboat, including the heavy engine compartment, was found 300m to the east of the Union Star, which suggests she met her fate here.

There was an unprecedented outpouring of sympathy for the bereaved. National recognition came with a visit by the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Locally, collection buckets overflowed as wallets and purses were literally emptied over them – the only practical help that could be offered by thousands of ordinary individuals to a shattered community.

Just two days after the Solomon Browne’s last service, a whole new crew of volunteers had come forward. This included the then 17- year-old Neil Brockman, son of the deceased Assistant Mechanic, and our current Mousehole Harbourmaster. Neil went on to be a Coxswain at Penlee. He and his new colleagues manned a relief Watson class Guy and Clare Hunter. In 1983, they received one of the new Arun class all weather lifeboats, the Mabel Alice. The yet larger and faster Severn class Ivan Ellen followed in 2003 alongside one of the new generation of inshore lifeboats.

In 1995 Neil was awarded the RNLI Bronze Medal for his part in the rescue of five men from a trawler off Land’s End. It was a proud day for him, his family and the people of Mousehole, highlighting the indomitable spirit of Cornish seafaring blood, and reminding the world that triumph is as much a part of Penlee lifesaving as tragedy.

Pirates, Smugglers & Privateering

Mousehole men earned the nickname of ‘Cut-throats’ for good reason – they weren’t just fisherman but often engaged in other illegal activities!

Smuggling was seen as a traditional legitimate activity by the Cornish for hundreds of years and stories of conflicts between resourceful smugglers and incompetent excise officers are part of local folklore.

Even when the Cornish drift net and seine fisheries were at their height, employing whole communities in the catching and curing of silvery shoals of pilchards (‘fairmaids’), many could not resist the temptation of smuggling, or, as it was more politely called, ‘free trading’.

Fast sailing luggers would slip quietly out of Mousehole to rendezvous with a Breton or Guernsey schooner, watchful of the revenue cutters, whose vigilant crews were adept at spotting contraband tea, a very valuable commodity, silks and wine, rolls of Virginia tobacco disguised as new potatoes or hollowed-out ballast stones filled with cognac. Caches of goods were ingeniously hidden all around the village and all classes of society were involved in the trade. There are many stories of men, detected by the revenue, coming up before a local magistrate who regularly received supplies of smuggled brandy.

Smuggling cases involving Mousehole people occur in most of the surviving customs book for the port of Penzance in the period 1738-1800. Two-thirds of the 70 named smugglers came from Mousehole.

Mousehole Village Clock

The village clock was installed on the top of the Mousehole Harbour Authority office in 1898.

It bears the name of Richard Treeve Harvey, a Mousehole man who spent many years living and working in Liverpool. He had a great love for his native village and paid for the clock with a large personal donation and a community collection. He came ‘home’ to Mousehole for his holidays each year and organised the first harbour sports & races for village children.

The Fitzroy Barometer

Situated in the wall of The Ship Inn is The Fitzroy Barometer – in 1854 it was ‘loaned’ to Mousehole by Admiral Robert Fitzroy, founder of the Meteorological Office.

It’s purpose was to provide data to the Met Office to improve storm warnings but also to give fishermen of the village warning of approaching bad weather. In the days before the BBC’s first shipping forecasts in 1924 fisherman relied on experience to forecast the weather.

In 2009, the Meteorological Office gifted the barometer to Mousehole Harbour Authority.

Vice Admiral Robert FITZROY (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy and a scientist. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of HMS Beagle during Charles Darwin’s famous voyage, Fitzroy’s second expedition to Tierra Del Fuego and the Southern Cone.